Climate changes and health

Direct effects from climate change include increased exposure to heat waves, drought extreme weather events, flooding, and fires.

Indirect environmental effects from climate change include increased exposure to microbial contamination, pollen, particulate air pollutants and carriers of new diseases.

Indirect social effects from climate change include disruption to health services, social and economic factors including migration, housing and livelihood stresses, food security, socioeconomic deprivation and health inequality.

The consequences of climate change are also expected to have adverse mental health and community health effects.

Who is most vulnerable to climate change?

The effects of climate change will not be spread evenly across the population, exacerbating existing socioeconomic and ethnic health inequalities.

The population groups most vulnerable include the elderly, infants and children, individuals with chronic health conditions, those of low socioeconomic status or experiencing homelessness, individuals living alone, and people with outdoor occupations.

Building blocks of health disrupted by climate change

- Mental outlook is important for health but repeated stresses from extreme weather and other impacts of climate change may take a toll on our wellbeing.

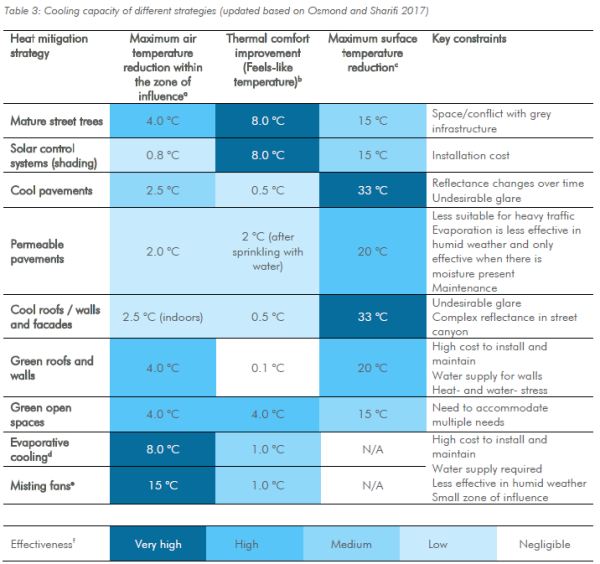

- Moderate temperatures make life and work comfortable but more hot days will increase heat stroke, aggression and heart disease, especially for the elderly, socially isolated, people with chronic illness and outdoor workers.

- We need healthy food but droughts, floods and changes in weather patterns increase risk of crop disease, food spoilage, shortages and food contamination.

- Clean water is essential for our health, but droughts and floods may cause shortages and increased temperatures may lead to more and longer toxic algal blooms.

- Sewage treatment and disposal systems can also be affected by flooding events, sea level rise and changes in rainfall patterns which may cause the environment to contaminated and increasing the risk of disease spread.

- Avoiding disease is vital for our health but rates of infection are likely to increase. Diseases already present in New Zealand such as campylobacter and cryptosporidium may become more prevalent and tropical diseases like dengue fever or West Nile virus may establish in New Zealand.

- People need adequate shelter for our health, but some homes, and potentially whole neighbourhoods and communities may become uninhabitable due to floods, erosion and fire. or be at risk from sea level rise and flooding.

- Clean air is vital for our health, but air quality is expected to decline, which will increase the prevalence of respiratory problems.

- Strong social ties support our health, but communities may be disrupted if neighbourhoods are abandoned or relocated. For example, due to sea level rise.

More information on the likely health effects of climate change in New Zealand can be found at Royal Society Te Aparangi.

Infographic : Health Impacts of Climate Change; Heatwaves